By Koinange Wahome

There is a quiet but consequential shift taking place in how power talks about corruption. It is no longer framed as a central economic failure. It is being reclassified as an inconvenience. That reframing matters because when ideas are voiced at the top of government, they do not remain opinions for long. They become signals.

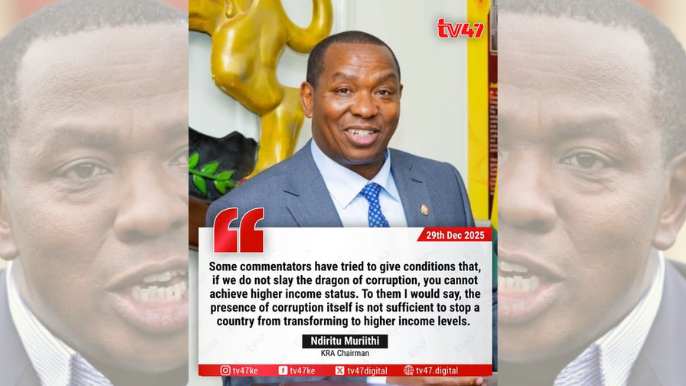

When Ndiritu Muriithi, the chair of the Kenya Revenue Authority Board, argues that corruption is “not sufficient to stop a country from transforming to higher income levels,” he is not thinking aloud. He is articulating a governing assumption from the institution that sits at the heart of state revenue.

When David Ndii, chair of the Presidential Council of Economic Advisers, publicly advances the same view, the message hardens. It stops being an individual perspective and becomes an organising idea within the state.

Two of the President’s most influential economic voices are converging on a single proposition: corruption can coexist with development and therefore should not dominate the economic conversation. That convergence is not accidental. It is instructive.

In government, what leaders downplay often matters more than what they denounce. When senior advisers repeatedly argue that corruption is survivable, they are not neutral. They are setting boundaries on enforcement, accountability, and political urgency.

If corruption is treated as manageable, then punishment becomes selective, reform becomes optional, and economic pain is explained away as structural or global. Over time, institutions adjust their behaviour accordingly. Tolerance travels downward.

The core problem with this argument is not moral blindness. It is economic misclassification. Corruption is not primarily an ethical issue. It is a market distortion.

In some contexts, tightly controlled corruption has coexisted with growth because rents were disciplined, predictable, and tied to performance. That is not Kenya’s reality.

Kenya’s corruption is systemic and extractive. It operates as an informal tax imposed through procurement, customs, licensing, and enforcement. It is paid not into the Treasury but to intermediaries whose power lies in blocking or facilitating access.

The results are familiar. Small businesses cannot compete without bribery. Investors price governance risk into every decision. Public projects cost more and deliver less. Employment shifts into informality, insecurity, and stagnation. Growth does not disappear. It is redirected upward, away from productivity and toward rent-seeking.

Supporters of this relaxed view often reach for international examples: South Korea, Singapore, Suharto’s Indonesia. The implication is simple. These countries grew despite corruption, so Kenya can too.

What is left out is enforcement context. South Korea disciplined its elites and jailed industrialists who failed to perform. Singapore allowed corruption no breathing room beyond its margins. Indonesia’s growth, unmoored from strong institutions, collapsed dramatically in 1997.

Kenya shares none of these characteristics. Its corruption is fragmented, short-term, and opportunistic. It rewards proximity to power, not output. To cite these cases without their coercive discipline is not comparative economics. It is storytelling stripped of consequences.

Kenya’s own data tells a consistent story. Manufacturing’s share of GDP has stalled. SME failure rates remain high. Capital inflows are cautious and expensive, priced for governance risk. Revenue collection struggles under leakages that push the burden onto compliant taxpayers.

These are not the markers of an economy on the cusp of transformation. They are the symptoms of one where rent extraction consistently beats production.

Downplaying corruption serves a political function. It lowers expectations of governance. It disconnects unemployment from policy failure. It recasts collapsed businesses as unfortunate casualties of global forces rather than predictable outcomes of local extraction.

This is accountability management, not economic realism. Entrepreneurs are told their struggles are structural. Young people are told growth is coming, just not yet and not necessarily for them. Citizens are told corruption is background noise, not the main act.

If corruption were merely an inconvenience, Kenya would not be watching factories shrink, foreign investors hesitate, youth unemployment harden, and SMEs suffocate under regulatory extortion. Corruption does not simply slow efficiency. It reshapes incentives.

No economy industrialises when procurement rewards loyalty over competence, tax enforcement is selective, customs clearance is negotiable, and credit flows to insiders rather than innovators. That is not transformation. It is managed stagnation.

The uncomfortable reality is that corruption is no longer just tolerated. It is being rationalised. It is softened through technocratic language and shielded through institutional inertia. When senior advisers publicly argue that corruption is not economically decisive, the message to the bureaucracy is clear.

To claim corruption does not block prosperity is to suggest that jobs can grow without fair markets, investment can thrive without the rule of law, and productivity can rise while theft is rewarded. Kenya’s history offers a blunt rebuttal.

Economic transformation is not produced by spreadsheets alone. It is produced by governance. Countries do not become prosperous despite corruption. They grow when corruption is costly, constrained, and socially unacceptable.

Any argument to the contrary is not hard-headed realism. It is political cover. And most Kenyans, living with closed factories, shrinking incomes, and narrowing opportunities, understand this instinctively, even when those closest to power insist otherwise.

Koinange Wahome is the County Secretary of the County Government of Laikipia